Gamification is a newer term being used in education to describe turning difficult or boring tasks into activities that contain features of traditional games. Although the term may be new, the concept is definitely not, and I think teachers and parents have been doing this for a long time to help reluctant learners.

I have been using games in my math classroom since I started teaching. I find that turning math learning into a game is very motivating for students who find rote practice boring and disengaging. I always do this with caution, however, because I am aware of how public competition can make some students feel. There’s a difference between friendly competition and embarrassing students who feel they aren’t strong math students. I avoid the latter by visibly and randomly grouping students together to play on teams. There is lots of research on visibly random groupings within the Thinking Classroom framework (Liljedahl, 2016) and I believe in its effectiveness because I’ve witnessed it in my classrooms. I also put a focus on improving as a group, rather than competing against others to win. With these two things in mind, I’ve successful gamified a lot of the math learning in my classroom.

Although I have been using games in the high school classroom for years, it was only in recent years that I learned their connection to growth mindset. I first read about this idea in The Growth Mindset Coach by Annie Brock and Heather Hundley, in the section title “Next-Level Mistakes: Game Not Over.” I don’t know why I never made the connection before, but it makes perfect sense. Brock and Hundley write,

“The cultural obsession with video games shows us that kids have the capacity to continually try for a goal even in the face of repeated failures, and yet many of the same children willing to spend hours mastering a level in a video game give up at the first sign of failure in school.”

This was exactly what I needed to hear to confirm that mastering math concepts through games is precisely what some children need.

At the time of reading this book, my own children were too young for video games, so I asked some students in my grade 10 class who I knew were big gamers to explain to me what they loved about video games. All of them said the same things:

- You get to keep trying and trying until you beat a level.

- Your status grows as you get further in the game and they like to brag about their status.

- You get to play with your friends.

Now our children, especially the 5-year-old, have started getting into video games and I see the perseverance already coming through when they are trying to beat a level. I’m amazed at how many times they can die and try again without getting angry.

Brock and Hundley suggest other ideas to implement from video games that help students stay engaged and get through something challenging: provide examples, allow “cheating,”, constant feedback, praise how long they stay with a problem rather than how quickly they finished it.

I’ve also been intrigued by the work of Jane McGonigal, an author and speaker who advocates for the use of gaming to increase your overall health and positivity. Check out her books and Ted Talks. She will convince you of the benefits of games in your life.

I find myself referring back to all of these ideas over and over again in the classroom when I need to remind my students to have a growth mindset when they meet challenges in their math learning.

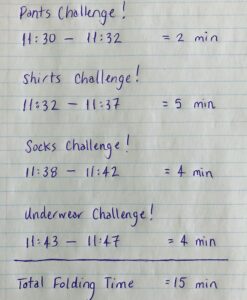

All of this has been on my mind because recently I’ve been struggling to get that same 5-year-old to do some of his regular chores, especially when it comes to his weekly laundry-folding task. He stomps and whines and insists that it takes too long and he can’t do it. And so, it finally occurred to me (and I’m embarrassed I didn’t think of it sooner) to turn it into a game. I did. And it was the simplest game I’ve ever made up.

We made a list of all the types of clothing he had to fold. We checked the time on the clock and recorded when he finished. He helped with telling the times and he calculated the minutes in between. And he raced to fold every piece of laundry in his pile, competing only against himself. We discussed all the math that came with it. The best part: the laundry was folded, and he did not complain at all.

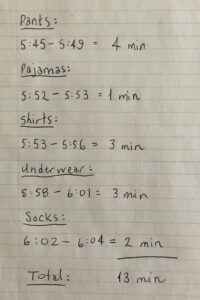

I thought it was a lucky fluke, but this past weekend, when it was time to fold laundry again, he and his sister took out two pieces of paper and asked if we could play the laundry game again. So, we did. The biggest lesson of all came when he made the revelation that it doesn’t take that long to fold laundry after all.

I encourage you to gamify your child’s next difficult or boring task. Remind them how beneficial games are to their overall perseverance.

Keep spreading the math love <3

![]()